Ducklings follow their mama in la Flor de Primavera.

A cat in the same village finds shelter from the rain and mud to groom.

A mona (monkey) in Nueva York eagerly checks the breakfast dishes for leftovers.

Defining the realities of community development:

The past week, Iveth and I left to work in the villages on Monday (a day earlier than usual) and returned on Friday (as usual). There was a medical group (an obstetrician, nurse, dentist, and health technician) present in both villages (la Flor de Primavera and Nueva York) and we were able to help and interact with them in their efforts. I will jot down several of my impressions and thoughts inspired from the week in the communities.

Medical service for the underserved:

Thoreau aptly noticed (or theorized) that there are hundreds hacking at the branches for every one who is striking at the root. Differentiating between the symptoms and root causes of ailment, I often end up feeling like a medical pecimist, but perhaps this is better than being indifferent if problems with the current system of care realisitcally exist. Allow me to put my jaggedly sharp words into context: The government-employed medical group that Iveth and I encountered in both villages this past week visits remote villages for a day or two with vaccinations, medicine, and basic dental treatments/exams. The majority of medicines that are perscribed are analgesics and antibiotics to treat cough, parasites, and other (including oral) infections. The dentist explains that she does not have the capacity cure cavities but that the patients should go to the city where dentists have the necessary equiptment to fill the cavities. In addition to occasionally exracting teeth and prescribing medications, she reminds children to brush their teeth thrice daily and applies flouride paste. Most villagers do not have an understanding of caries formation and the progression of such an infection into the pulp of the tooth. As a future dentist, I felt like more should have been done to meet the oral health needs of the villagers. It is understandable that certain technological aids are not compatible with clinical work in remote regions; but approaching this reality from the educational side, I think more can be done. Ignorance of basic oral phenomena (the connection between oral hygiene, bacterial infection, and tooth destruction/pain) serves, to me, as a red flag. It does not make sense to function under a symptoms-driven, treatment-emphasized system of care in a locale where access to resources and health care are limited. In such a situation, does it not make more sense (than ever--as education is always foremost) to target and 'treat' with education as a way of preventing disease that may be difficult to cure (due to isolation from resources and care)? I pondered in a similar manner about parasite medications given to nearly all children over the age of 1. The antibiotic may clear their intestines of microflora (good and bad) for a day or two (not likely relieving them of diarrhea); but, more importantly, they are still drinking from the same pila, where the water is continually contaminated by inadequate waste management (inappropriate latrine design and animal containment). With such a quick relapse of infection, the prescribed antibiotics seem to be doing little more than running 'the parasiticide treadmill,' producing antibiotic-resistant parasitic organisms that adversely affect a population of people who will not see a medic for an indefinite length of time. Perhaps similar questions can be raised for other medications prescribed in the absense of ensuring the prevention of recurrent ailment. Although composed of native Peruvians and funded by the government of Peru, is this 'mini brigade'-styled system of care using medical hands and financial resources wisely? Is it worth spending these resources sparsely (although not sparingly) in populations that are generally isolated from them? Whatever the answers to these questions may be, the villagers eagerly accept the free services. They intently listen to diagnoses of chronic malnutrition, parasites, and other infections, accept the medications and/or treatment that is offered, and hear out what further treatments and medications could be offered to them in the city (where they will not likely go to seek health care). Contrasting the willingness to wait all day to receive a package of tablets with the difficulty Iveth and I experienced in gathering villagers for meetings and workshops, I found it frustrating that the 'bandaid' offered by the group of medics was so readily accepted and applied while there is no perceived beauty or importance in self-empowerment and the sustainabl development of holistic health. Interacting with the village-commited technician in the health center of la Flor de Primavera, Zenaida, I got a sense of the difficulty of her job. She faces adversity in attending to the needs of the community, both with the villagers' resistence to modification of their lifestyles and seeking care as well as the limited support for which she must lobbey from the city health departments. Assisting Iveth in the family workshops (where she describes the components of a healthy family and helps villagers acknowledge existing needs and set realistic goals to meet them), I was discouraged at the lack of motivation in the meeting. Many families were represented by only mom or dad and some were very passive in applying the process to their family, waiting to be instructed what goals to write or what vision to propose. I wondered how Zenaida, the health technician, stays motivated to improve the village's health when they do not 'meet her halfway.' I suppose working 'along the margins,' attending to the brokenness (the physical, relational, and elcological ailment) of a remote region's population, is not a glorious or simple venture. Thinking about one's own professional satisfaction, it might be difficult to list the benefits of working in underserved and isolated communities. However, I am reminded that Jesus intentionally found himself ministering at the margins of society, where he was most needed. If one is intent on emulating his conduct, the following question might emerge: "How much (if at all) am I willing to 'lay my life down' for those who might not appreciate my efforts?" But we also might remember that in sparing our life, we ultimately lose it, while preservation results from its loss.

Iveth and I visited a schoolroom in la Flor de Primavera to show health educational videos via laptop and projector.

A preschool class in Nueva York washes their hands before a snack. We later visited the kids to practice tooth-brushing.

Visiting homes to gauge the condition of thier kitchens and latrines, we encountered a señora spinning lino (thread).

A young girl in la Flor de Primavera busily pens in the kitchen.

A typical village kitchen (there are more and less complex versions). Having smoke inside the house causes lung and eye problems but seems to offer a place to smoke meat (hanging above the stove top).

Many kitchens house chickens, ducks, and cuys (guineas).

The warmth of the stove helps the cuys thrive and reproduce more quickly (we were told).

Another (more spacious and simple) styled stove. I think yucca awaits cooking at the right.

Somewhere in the back yard, there is usually a latrine similar to this one.

Several commmunity families from la Flor de Primavera gather for a workshop to identify needs and set goals to attain a healthy family.

Two señores contemplate on their families' goals for the year.

Iveth explains what perameters describe a healthy family.

Some children also attended the workshop, helping the elders with penmenship.

The last merienda in Nueva York:

Although I was discouraged at the lack of interest and motivation in many of the villagers towards sustainably improving their lives through the community development workshops that we offered, I was enchanted by several aspects of village life. Visiting the villages for the third week, Iveth and I are starting to become familiar with several families in the communities. In la Flor de Primavera, an older couple who has a small warehouse (bodega) business offers their hospitality for our meals in the village. Although they both likely have only elementary school education (reflected in their struggle to spell various words while composing their vision and goals at the first family workshop), they keep their house, business, farm fields, and yard in wonderful order, always looking for ways to improve (they have prepared a raised bed in their yard to plant a house garden in the summer). Several of their children study in the city's high school. This is an expensive commitment for the family, but reflects their striving to do well in their current situation. Sharing several meals with Zenaida at this family's table, I enjoyed listening to 'village talk,' the simple but intimate care and knowledge regarding neighbors (their joys, troubles, and how they affect the community). I tried to imagine what it would be like to be surrounded by the same 150 people day in and day out at school, work, church, field, and street. My hope is that the close proximity of such a number of people yields a mutually supportive community, but I fear (due to hearing about drinking, marital, and overall health problems) that the village, which should resemble a big family, is broken and scattered, each member absorbed in his own interests and vulnerabilities.

The powerlines were being repaird (as it was explained to us) in la Flor de Primavera but the technician still went to work in the pharmacy after supper, filling out various forms and reviewing charts by candle-light. In Nueva York, there is only electrical light from 6:30-9:30pm, provided by a gas-run generator (which did not have adequate fuel when we arrived). Although I am not sure the I could easily give up internet, email, and other computer processing functions, I enjoyed being dependent on the cycles of the sun. [Disclaimer: this kind of life might work better in Peru because the sun rises at 6am and sets at 6pm year round]

After helping the medical team attend to patients in Nueva York (many impatient mothers and screaming children, who were threatened with 'more vaccinations if they wouldn't quiet down'), I enjoyed watching a family prepare an evening meal with flashlights and candles. The father had accompanied the medical team in their travel to the next village and the mother of the family and her cousin prepared rice with a fried potatoe/canned liver mixture, while two young girls attended to their baby sister in a dark neighboring room (the eldest, 11, scared the 1 year-old when she fussed, imitating the medical workers by saing, "Who's this cry baby? Where is a vaccine that we can give her?" She would follow with a song about Jesus' love to calm the baby). The girls soon emerged and the baby was strapped with a cloth to her mother's back (as most Peruvian children are carried). The eldest stood by a candle and read aloud from one of her old text books and helped with the meal as necessary. It brought me great pleasure to see a group of people functioning together in harmony, each responding naturally to arising necessities and fulfilling them with such care and enjoyment. After being discouraged by thoughts of futility and helplessness while assisting in the mini medical brigade, I felt comforted to see such enriched life and love in the household. Considering the merienda as possibly my last supper in the village, I though about the last supper in the gospels and in how similar a scene I was participating. The passover meal shared amongst disciples and teacher must have been saturated by Jesus' life-enriching words and the love that he shared with his disciples (especially John). However, the reality of Jesus' imminent death was not excluded from the meal; Judas was prepared to fulfill his unfortunate plan. While we shared a merienda (evening meal) with the family in Nueva York, the less-than-ideal realities of village life were still present. A piglet wandered through the kitchen, mosquitoes and various insects circled the candle, our food, and our bare skin, and the girls crossed the dirt floor barefooted. Ailment, if not already present, might be around the corner, but the family gathered, sitting on sacks of rice or a wooden bench, to share a meal (both sharing and the meal being valuable).

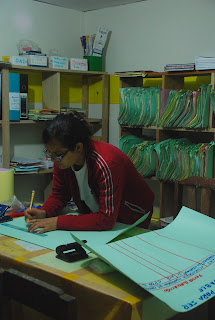

Iveth prepares more posters for the family workshops. In la Flor de Primavera, we stay in the pharmacy/chart room of the mini health center that is run by Zenaida, a health technician.

Our sleeping arrangement in la Flor de Primavera.

In a building near the church, which accomodates us during our visits in Nueva York, stand several seemmingly unused boxes of donations. It seems that poverty (at least in this village) requires a different approach at alleviation.

Below are quotes that I noted from Wendell Berry's compilation of essays On Farming and Food: Bringing it to the Table. Although he is concerned mostly with agriculture, he points out the relationship between agriculture and health, claiming that the two are really one great subject. In taking interest in the agricultural application of his thoughts, I was often able to apply the themes to health care and community development.

"The word "sustainable"...I suggest, refers to a way of farming that can be continued indefinitely because it conforms to the terms imposed upon it by nature of places and the nature of people" (Stupidity in Concentration, 2002).

"Its [--a farm's--] needs were kept within the limits of its resources" (Energy in Agriculture,1979).

"Not long ago I heard an economist say, "If the consumer ever stops living beyond his means, we'll have a recession" " (Conservationist and Agrarian, 2002).

"Spending money gives one status. And physical exertion for any useful purpose is looked down upon; it is permmissible to work hard for "sport" or "recreation," but to make any practical use of the body is considered beneath dignity" (Sanitation and the Small Farm, 1971).

"We cannot keep things from falling apart in our society if they do not cohere in our minds and in our lives" (Renewing Husbandry, 2004).

"The balance between growth and decay is the sole principle of stability in nature and in agriculture. And this balance is never static, never fully acheived, for it is dependent upon a cycle, which in nature, and within the limits of nature, is self-sustaining, but which in agriculture must be made continuous by purpose and by correct methods" (on The Soil and Health, 2006).

"It was borne in on me that there was a wide chasm between science in the laboratory and practice in the field, and I began to suspect that unless this gap could be bridged no real progress could be made in the control of plant diseases: research and practice would remain apart: mycological work threatened to degenerate into little more than a convient agency by which--provided I issued a sufficient supply of learned reports fortified by a judicious mixture of scientific jargon--practical difficulties could be side-tracked" (The Soil and Health, Sir Albert Howard).

"After all, the destruction of a pest is the evasion of, rather than the solution of, all agricultural problems" (Sir Albert Howard in India).

"...the guiding principle of the closest contact between research and those to be served" (Ibid, Sir Albert Howard).

"The most important posession of a country is its population. If this is maintained in health and vigour everyting else will follow; if this is allowed to decline, nothing, not even greater riches, can save the coutnry from eventual ruin" (An Agricultural Testament, Sir Albert Howard).

"First, neither farming nor experimentation should usurp the tolerances or violate the nature of the place where the work is done; and second, the work must respect and preserve the livelihoods of the local community. Before going to work agricultural scientists are obliged to know both the place where their work is to be done and the people for whom they are working...enfolded consciously and conscientiously within the natural and human communities that he endeavored to serve" (on the Soil and Health, 2006).

" "Life is not very interesting," we seem to have decided. "Let its satisfactions be minimal, perfunctory, and fast." We hurry through our meals to go to work and hurry through our work in order to "recreate" ourselves in the evenings and on weekends and vacations. And then we hurry, with the greatest possible speed and noise and violence, through our recreation--for what? To eat the billionth hamburger at some fast-food joint hellbent on increasing the "quality" of our life? And all this is carried out in a remarkable obliviousness to the causes and effects, the possibilities and the purposes, of the life of the body in this world" (The Pleasures of Eating, 1989).

Mules, such as these two, are used to cary heavy loads when cars cannot venture through the muddy roads.

Just as the sun began to set, the rain came. It was persistent through the night and left the roads very soft for our trek back to the city on Friday morning, resulting in at least two splendid slip-and-fall and sinking-into-slop events on my part.

On the way down the mountain to the city, the beauty of the Selva region presented itself.

Getting accross the river Mayo requires the sevice of these canoe moats, which also carry loaded pickups, mules, and moto taxis across.

During the last full week of my internship, I will visit several more schools with my mini dental lessons...and I can't help but mention my patient eagerness to return to home and family!

No comments:

Post a Comment